Sugary Surprise nets UURAF Grand Prize

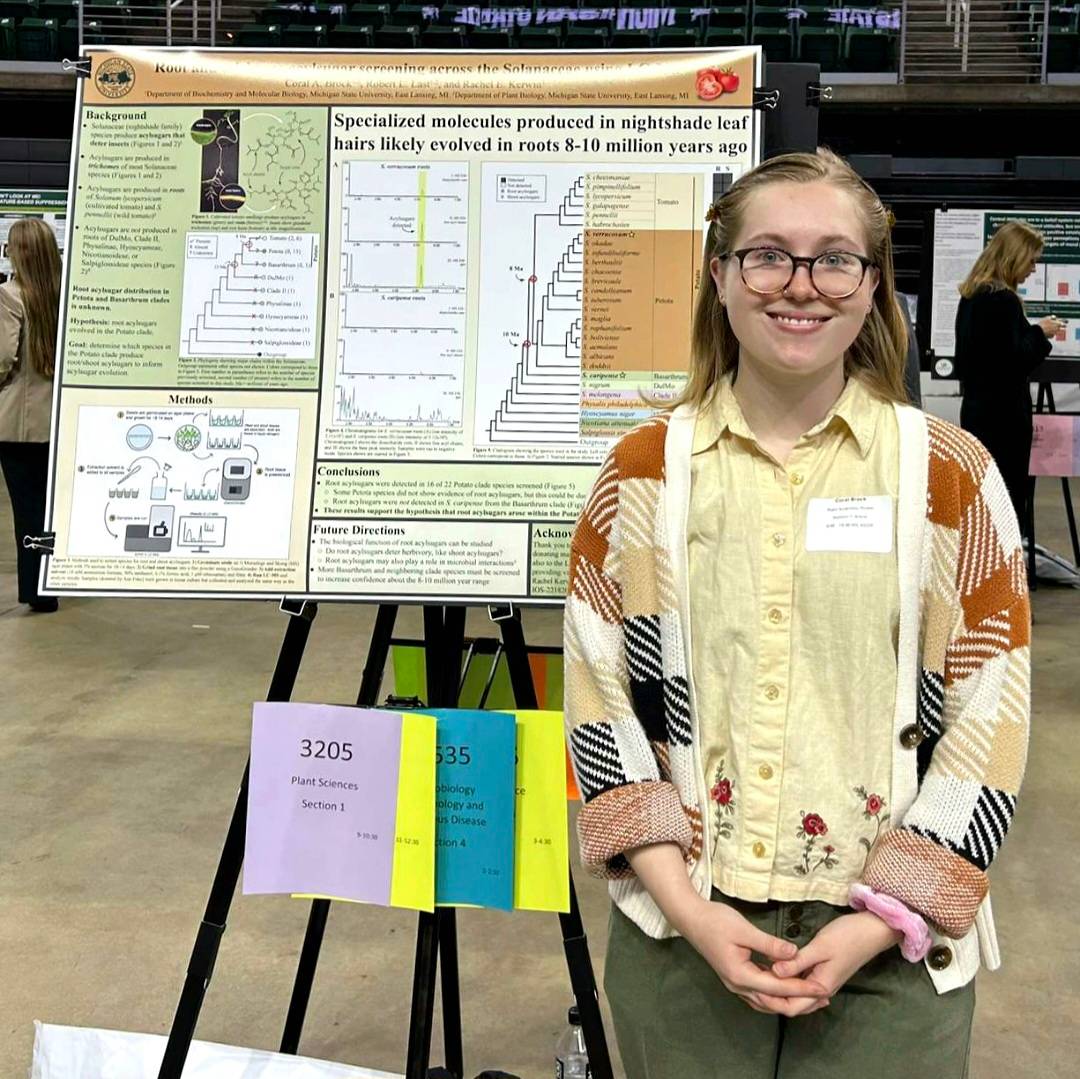

Coral Brock, a 2024 graduate of the Plant Biology program, won the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Grand Prize at the 2024 University Undergraduate Research and Arts Forum, or UURAF.

UURAF provides undergraduate students from across the University with an opportunity to showcase their research.

For her award-winning project, Root and Shoot Acylsugar Screening Across the Solanaceae Using LC-MS, Brock screened the roots of various plants within the nightshade family, Solanaceae — which includes tomatoes, potatoes and eggplants — to search for compounds called acylsugars.

These compounds, which are unique to nightshades, are produced on the tips of trichomes: microscopic hair-like structures that grow on some plants’ leaves and stems.

Acylsugars are suspected to perform multiple functions across the plants that produce them. They often deter predators, for example; acylsugars can be toxic to herbivores, and their sticky consistency can trap insects that might otherwise cause damage.

Until recently, acylsugars were thought to be produced only in the secretory glands at the tips of trichomes. New evidence shows that acylsugars are produced in the roots of some nightshades as well.

However, roots lack trichomes, and don’t face the same stressors as plants’ aboveground components. Now, questions as to how, why and where root acylsugars are produced are the subject of interest in nightshade research – including in the Last lab at MSU, where Brock undertook this project.

Solanum pennellii (Tomato) leaf glandular trichomes at 60x magnification. Credit: Coral Brock.

Root acylsugars are distinct from their above-ground counterparts in both how and why they are produced. As part of the puzzle, researchers in the Last Lab are trying to better understand when the production of these specialized compounds emerged.

Rachel Kerwin, Brock’s research mentor, co-principal investigator on the project and a postdoctoral researcher in the Last lab, explained the rationale behind the project:

“One question we wanted to answer with Coral's project is, what other species also produce root acylsugars? We want to understand when and how root acylsugars evolved, and determining their distribution is an important part of this process.”

To help shed light on this mystery, Brock examined the roots of various nightshades using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, or LC-MS, to identify whether acylsugars were present in the plants’ roots.

Kerwin extolled Brock’s efforts, explaining that Coral tracked down seeds for many of the study species, and then “grew seedlings, collected tissue, extracted metabolites, performed liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, and analyzed all the data to determine which species accumulated root acylsugars.”

After investigating 22 species in the potato clade — a group of closely related species derived from a common ancestor — Brock discovered acylsugars in the roots of 16 of the 22 species.

Brock’s findings help fine-tune estimates of when root acylsugar production emerged, by determining where along the phylogenetic tree species began producing these compounds.

The results revealed that acylsugars were present in the roots of all species in the Tomato sub-clade, as well as some wild potato species, but not in domesticated potatoes (Solanaceae tuberosum). Now, Brock explained, “we have evidence to support the hypothesis that root acylsugar evolution began somewhere between 8 and 10 million years ago. Previous estimates hypothesized 8 to 13 million years ago.”

“With Coral’s data included, we now have root acylsugar phenotypes for nearly 30 Solanaceae species,” Kerwin said.

Come fall, Brock will begin a master's program at Northwestern University in Plant Biology and Conservation. There, Brock will be working under Hector Ortiz on a project to start a community garden in Chicago’s Southside neighborhood.

“We are collaborating with a team to start a community farm/garden on the south side of Chicago, where we'll be studying culturally important plants and how they are affected by climate change,” Brock said.